The Jewish New Year celebrations are over, and now the Jewish community is gearing up for the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur, which starts on Friday evening. Here, Vicki Belovski, journalist and Nisa-Nashim member & volunteer, explains about her own experiences of Yom Kippur, and what the holiest day in the Jewish year means to her.

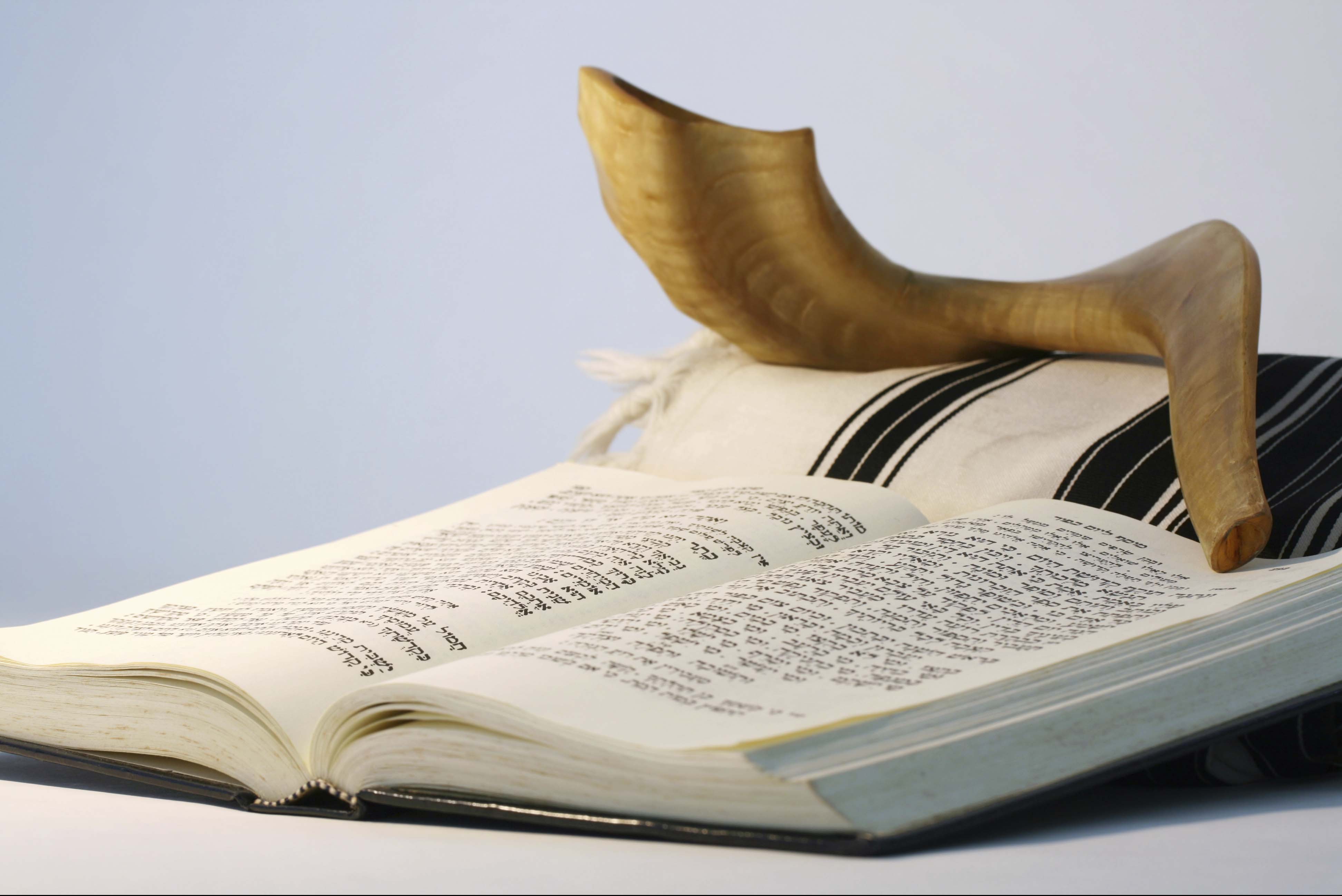

“Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, is the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. It is the day on which we are guaranteed forgiveness for our sins, both personal and communal, as long as we truly repent, and on which, as Caroline said, our personal decree for the forthcoming year, which was written on Rosh Hashanah, is sealed. On Yom Kippur, we are considered to be like angels, so we don’t eat or drink and many people wear something white, but we are also commanded to afflict our souls, so we refrain from certain other acts, such as wearing leather shoes or washing for pleasure. We also observe the Shabbat restrictions, as Yom Kippur is considered to be the Sabbath of Sabbaths.

My husband, Harvey, is a communal rabbi, and so for him, it is one of the most intense work days of the year, with around 15 of the 25 hours spent in synagogue, leading the prayers, speaking, doing a question and answer session, encouraging and inspiring the congregation and trying to get in some personal prayer around all that. With this in mind, when I add that 15 years ago, on Yom Kippur, our youngest daughter was born, you’ll see why it was such a big deal!

When I woke up that morning and said, “I think the baby’s coming!”, our contingency plan swung into action. We had a team of people on standby to look after our other children, and Harvey watched out of the window for the friend who was supposed to be assisting in running the services to walk past, so he could tell him that he wasn’t assisting – he was running the show! When the rabbi didn’t appear in synagogue that morning, word quickly spread, and soon, some 300 people knew I was having a baby!

As the day wore on and she didn’t emerge, Harvey, who of course was fasting, and trying to fit in prayers round contractions, muttered something on the lines of, “This baby had better actually come today!” But fortunately, in the late afternoon, our daughter arrived, in time for him to spend some time with us, walk home (an hour’s walk, in canvas shoes, leaving him with considerable blisters) and tell the children before the festival ended.

That was our most remarkable Yom Kippur ever, and it has a knock-on effect till today. (Apart from people still asking her if she’s the Yom Kippur baby!) Given that it’s a 25 hour fast, we eat a substantial meal in the late afternoon of the previous day (usually chicken soup with kreplach, meat-filled triangular ravioli, followed by chicken, and a light dessert). This meal tends to be family only, although we sometimes have a couple of guests who will be joining us in synagogue. Then when the fast ends, family and friends gather for the break fast meal, which generally begins with tea and cake, followed by a proper meal, with the menu depending on the family’s traditions and preferences. In our house, we have tea and birthday cake with candles. We also give birthday presents then and have even been known to have impromptu concerts, when guests have brought a guitar…

The mood at this meal is quite festive anyway – people are simultaneously tired from the long day and still buzzing from the emotions. The prayers on Yom Kippur are very intense with ample time for personal reflection, as well as lots of communal singing to well-loved tunes. The feeling of several hundred people singing together, with tunes that only appear once a year, which they have known from childhood, is something quite unique. And the sense of drama as we progress through the day, from anticipation, to relief when we reach the concluding service, which focusses on the fact that the gates of repentance are closing, and we must make a final effort, is incredible.

Many people are moved to tears during the day, and the last hour or so is always very emotional. Tradition has it that if you feel a sense of lightening and relief, during the final prayer service, it’s a sign that your prayers have been accepted. When we shout out the final phrases of the prayers, declaring the unity of God and accepting His dominion over us, the whole building reverberates. The service concludes, at the end of the festival, with sounding the shofar, the ram’s horn, often followed by singing and dancing. Then, the congregation wishes each other a good year, and gradually disperses home, to break their fast, and begin to prepare for the next festival – Sukkot, just a few days away…”